Psychometrics refers to an area of statistics focused on developing, validating, and standardizing tests, though it can also refer to a methodological process of creating tests, beginning with identifying the exact construct to be measured, all the way up to continuing revision and standardization of test items. As institutions become more and more data-driven, many are looking to hire psychometricians to serve as their measurement experts. This is an in-demand field. And psychometrics is still a rather small field, so there aren’t a lot of people with this training.

For this post, I focused on my own journey – since the only experience I know well is my own – but I plan to have future posts discussing other tracks colleagues (both past and present) have taken. My hope is to give you, the reader, some guidance on entering this field from a variety of starting places.

To tell you more about myself, my journey toward becoming a psychometrician could probably begin as early as 2002-2003, my junior year in college, when I first encountered the field of psychometrics. But it wasn’t until 2014 that I really aimed at becoming a psychometrician, through post-doctoral training. And though I’d been calling myself a psychometrician since at least 2014, I took my first job with the title “psychometrician” in 2016.

Of course, it may have begun even earlier than that, when as a teenager, I was fascinated with the idea of measurement – measures of cognitive ability, personality, psychological diagnoses, and so on. I suppose I was working my way toward becoming a psychometrician my whole life; I just didn’t know it until a few years ago.

But I may ask myself:

Undergrad

I majored in Psychology, earning a BS. My undergrad had a two-semester combined research methods and statistics course with a lab. While I think that really set the foundation for being a strong statistician and methodologist today, I also recognize that it served to weed out many of my classmates. When I started in Research Methods I my sophomore year, I had over 30 classmates – all psychology majors. By Research Methods II, we were probably half that number. And in 2004, I graduated as 1 of 5 psychology majors.

During undergrad, I had two experiences that helped push me toward the field of psychometrics, both during my junior year. I completed an undergraduate research project – my major required either a research track (which I selected), involving an independent project, or a practitioner track that involved an internship. This project gave me some hands-on experience with collecting, analyzing, and writing about data, and is where I first learned about exploratory factor analysis, thanks to the faculty sponsor of my research. And that year, I also took a course in Tests & Measures, where I started learning about the types of measures I would be working on later as a psychometrician.

At this point in my career, I wasn’t sure I wanted to go into research full-time, instead thinking I’d become a clinical psychologist or professor. But I knew I enjoyed collecting and (especially) analyzing data, and this is when I first started spending a lot of time in SPSS.

Spoiler alert: I use SPSS in my current job, but it’s not my favorite and in past jobs, I've spent much more time in R and Stata. But it’s good to get exposed to real statistical software

1 and build up a comfort level with it so you can branch out to others. And getting comfortable with statistical software really prepared me for…

Grad School

After undergrad, I started my masters then PhD in Social Psychology. I had applied to clinical psychology programs as well, but my research interests and experience (and lack of clinical internship) made me a better fit with social psychology. My goal at that time was to become a professor. Since I had a graduate assistantship, I got started on some research projects and began serving as a teacher assistant for introductory psychology and statistics. This is where I began to fall in love with statistics, and where I first had the opportunity to teach statistics to others. Many students struggled with statistics, and would visit me in office hours. Working to figure out how to fix misunderstandings made me learn the material better, and turning around and teaching it to others also improved my understanding.

I took basically every statistics course I could fit into my schedule, and tacked on a few through self-designed candidacy exams, workshops at conferences, and self-learning for the fun of it: multivariate statistics, structural equation modeling (including an intermediate/advanced 3-day workshop paid for with monetary gifts from Christmas and birthday), meta-analysis, power analysis, longitudinal analysis, and so on and so on. Surprisingly, I didn't delve into modern test theory and I can't remember if I'd even heard of item response theory or Rasch at this point, but I was only looking around the psychology scene. Those approaches hadn’t reached a tipping point in psychology yet and, honestly I’m not sure they’ve reached it yet even now, but we’re much closer than we were a decade ago.

I also became more exposed to qualitative research methods, like focus groups and interviews, and how to analyze that kind of data, first through a grant-funded position shortly after I finished my masters degree, and then, during my last year of graduate school, as a research assistant with the Department of Veterans Affairs. (By that point, I’d given up on being a professor and decided research was the way I wanted to go.) And that position as a research assistant led directly to…

Post Doc #1

Post-doc #1 was part of a program to train health services researchers. But I had some freedom in designing it, and devoted my time to beefing up my methods skills, becoming someone who could call herself an experienced qualitative (and mixed methods) researcher. I trained people on how to conduct focus groups. I coordinated data collection and transcription of hundreds of focus groups and interviews over multiple studies. I analyzed a ton of qualitative data and got more comfortable with NVivo. I brought innovative qualitative research methods to VA projects. And I published a lot.

A bit before my last year of post-doc #1, I became involved with a measurement development project using Rasch. I was brought on board for my qualitative expertise: to conduct and analyze focus groups for the first step in developing the measure. I was intrigued. I knew all about classical test theory, with its factor analysis and overall reliability. But this approach was different. It gave item-level data. It converted raw scores, which it considered ordinal (something I’d never thought about), into continuous variables. It could be used to create computer adaptive tests and generate scores for two people that are on the same metric even if the two people had completely different items. It was like magic.

But better than magic – it was a new approach to statistics. And as with statistical approaches I’d encountered before that, I wanted to learn it.

Fortunately, the Rasch expert for the study was a friend (and a colleague who thought highly of me and my abilities), and she took the time to sit down and explain to me how everything worked. She let me shadow her on some of the psychometric work. She referred me to free webinars that introduced the concepts. She showed me output from our study data and had me walk through how to interpret it. And most of all, she encouraged me to learn Rasch.

So I wrote a grant application to receive…

Post Doc #2

That’s right, I did 2. Because I’m either a masochist or bat-s*** crazy.

But this time, I had a clear goal I knew I could achieve: the goal of becoming a full-fledged psychometrician. As such, this post-doc was much more focused than post-doc #1 (and was also shorter in length). I proposed an education plan that included courses in

item response theory and

Rasch, as well as a variety of workshops (including some held by the

Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago and the

PROMIS project). I also proposed to work with a couple of experts in psychometrics, and spent time working on research to develop new measures. I already had the qualitative research knowledge to conduct the focus groups and interviews for the early stages of measure development, and I could pull from the previous psychometric study I worked on to get guidance on the best methods to use. In addition to my own projects, I was tapped by a few other researchers to help them with some of their psychometric projects.

Unfortunately, the funding situation in VA was changing. I left VA not long after that post-doc ended, in part because of difficulty with funding, but mainly, I wanted to be a full-time psychometrician, focusing my time and energy on developing and analyzing tests.

Fortunately, I learned about an opportunity as…

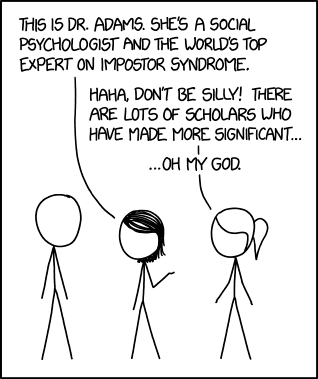

Psychometrician at Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

When I first looked at the job ad, I didn’t think I was qualified, so I held off on applying. I think I was also unsure about whether a private corporation would be a good fit for me, who had been in higher education and government for most of my career at that point. But a friend talked me into it. What I learned after the interview is that 1) I am qualified and that self-doubt was just silly (story of my life, man), and 2) the things I didn’t know could be learned and my new boss (and the department) was very interested in candidates who could learn and grow.

Fortunately, I had many opportunities to grow at HMH. In addition to conducting analyses I was very familiar with – Rasch measurement model statistics, item anchoring, reliability calculations, and structural equation modeling and other classical test theory approaches – I also learned new approaches – classical item analysis, age and grade norming, quantile regression, and anchoring items tested in 2 languages. I also learned more about adaptive testing.

A few months after I started at HMH, they hired a new CEO, who opted to take the company in a different direction. In the months that followed, many positions were eliminated, including my own. So I got a 2 month vacation, in which I took some courses and kept working on building my statistics skills.

Luckily, a colleague referred me to…

Manager of Exam Development at Dental Assisting National Board

DANB is a non-profit organization, which serves as an independent national certification board for dental assistants. We have national exams as well as certain state exams we oversee, for dental assistants to become certified in areas related to the job tasks they perform: radiation safety (since they take x-rays), infection control, assisting the dentist with general chairside activities, and so on. My job includes content validation studies, which involves subject matter experts and current dental assistants to help identify what topics should be tested on, and standard setting studies, once again involving subject matter experts to determine pass-points. I just wrapped up my first DANB

content validation study and also got some additional Rasch training, this time in

Facets.

Going forward, I’m planning on sharing more posts about the kinds of things I’m working on.

For the time being, I’ll say it isn’t strictly necessary to beef up on methods and stats to be a psychometrician – I’m an anomaly in my current organization for the amount of classical stats training I have. And in fact, psychometrics, especially with modern approaches like item response theory and Rasch, is so applied, there are many psychometricians (especially those who come at it from one of those applied fields, like education or healthcare) without a lot of statistics knowledge. It helps (or at least, I think it does) but it isn’t really necessary.

That's what brought me here! Stay tuned for more stories from fellow psychometricians in the future. In the meantime, what questions do you have (for me or other psychometricians)? What would you like to learn or know more about? And if you're also a psychometrician (or in a related field), would you be willing to share your journey?

1Excel, while a great tool for some data management, is not real statistical software. It's not unusual for me to pull a dataset together in Excel, then import that data into the software I'll be using for analysis.